Monitoring climate seems distantly related to the work of the Alaska Earthquake Center, but it can actually improve our seismological studies. Climate data collected from sensors on existing stations gives us better insight into our seismic signals, helps us construct better seismic stations, and opens up new avenues of research. From Arctic winds to Bering Sea storms, semi-constant vibrations can mask seismic signals from larger events like earthquakes or other features that our analysts decipher. But sometimes, those small vibrations can be the signal that carries an interesting story.

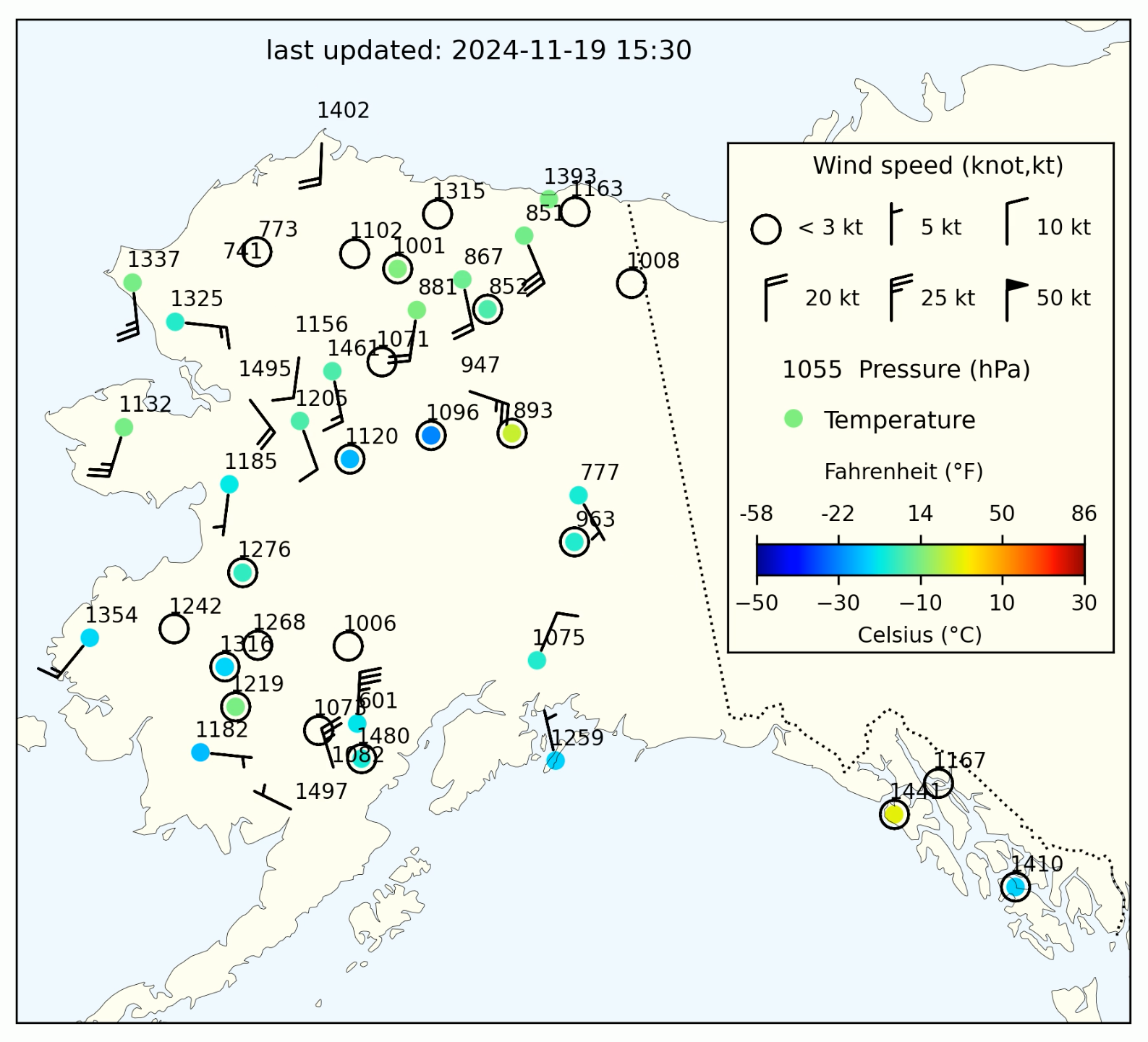

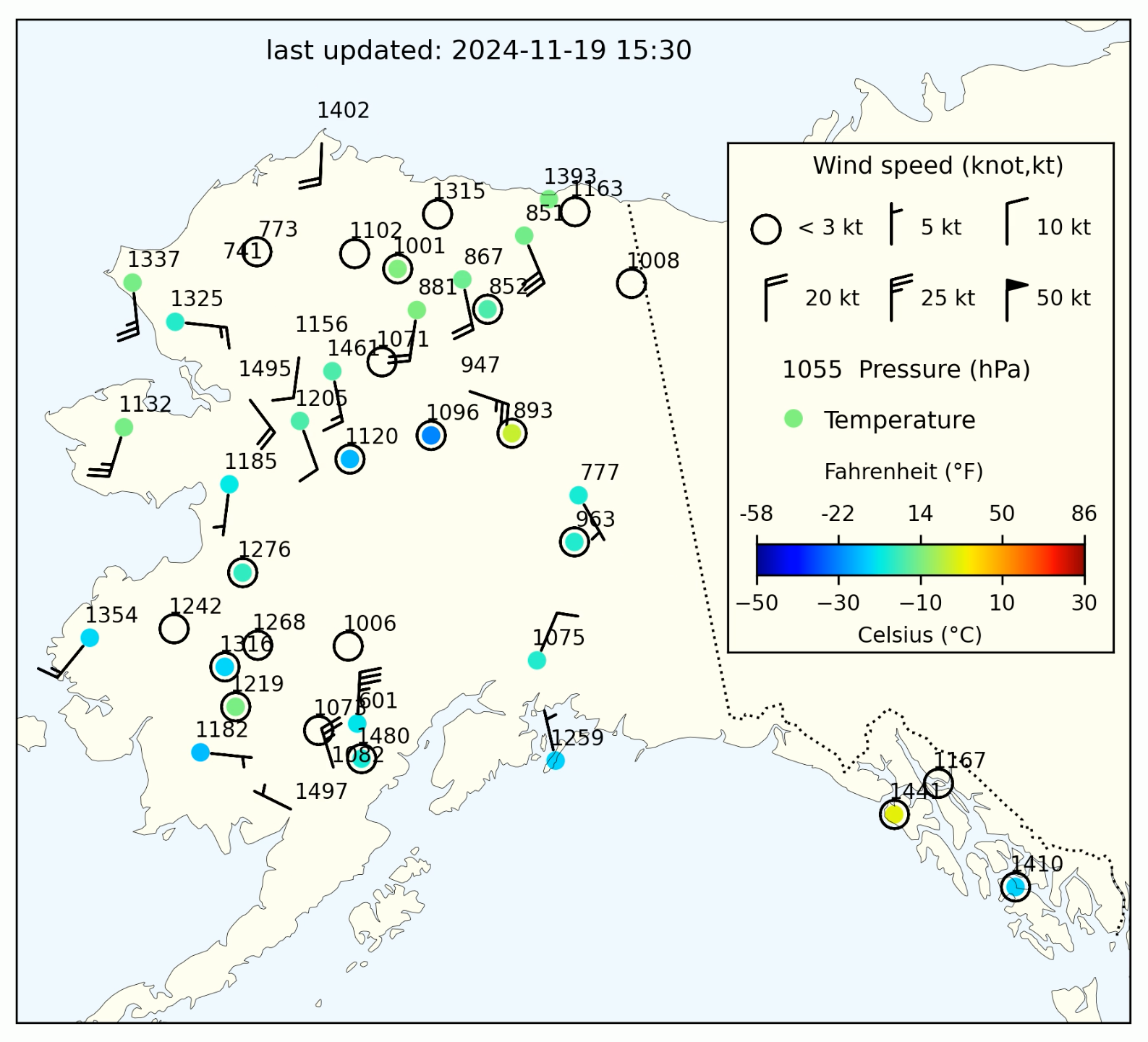

When the Alaska Earthquake Center adopted almost 70 stations equipped with weather instrumentation (Figure 1) from the USArray in 2021, we embraced the opportunity to start providing weather information in real time. “It is very easy for us to implement weather into our existing infrastructure,” says Mike West, the Director of the Alaska Earthquake Center, “and, when we do it right, it creates new research and partnership opportunities to better understand our changing climate and how it impacts geologic hazards.”

The Alaska Geophysical Network, with over 250 stations that span Alaska, provides real-time observations from each station, many of which host multiple instrument types.

One example of how climate sensors co-located with seismic instruments yielded insight into environmental imprints on seismic data came from research by Earthquake Center graduate student Cade Quigley. This study showed that wind speed, vegetation, storm systems, snowpack, and seasonality all influence seismic noise. The noisier the data, the slower and harder it is for our analysts to pick out the larger signals, like those from earthquakes or explosions.

Discovering that seismic noise is associated with weather signals also means that the co-located instruments are observing the changing Arctic environment as it warms significantly faster than the rest of the globe. In addition to weather data, which shows emerging patterns like longer snow-free seasons and increased vegetation growth (Figure 2), we also use soil temperature probes to help measure the thawing of permafrost and glaciers.

Research seismologist Ezgi Karasözen, who focuses on monitoring landslides, notes the important role that climate-monitoring instruments play in more fully understanding Alaska’s unstable slopes. "The warming climate is causing glaciers to retreat, leaving valleys whose mountainsides and hillsides have lost their support," she says. As a result, regions of southern coastal Alaska are at risk for landslides including those that cause tsunamis.

The data we collect is publicly available and used by organizations outside the Alaska Earthquake Center. The Wilson Alaska Technical Center and the Arctic Climate Research Center are a couple of local examples of those who utilize our data. We send our data to the MesoWest program, which provides public access to weather observations that are also used by National Weather Service meteorologists across the western United States. The Alaska Interagency Coordination Center uses the data to calculate fire risk in remote areas of Alaska. Live weather map apps, including Windy, show our weather data.

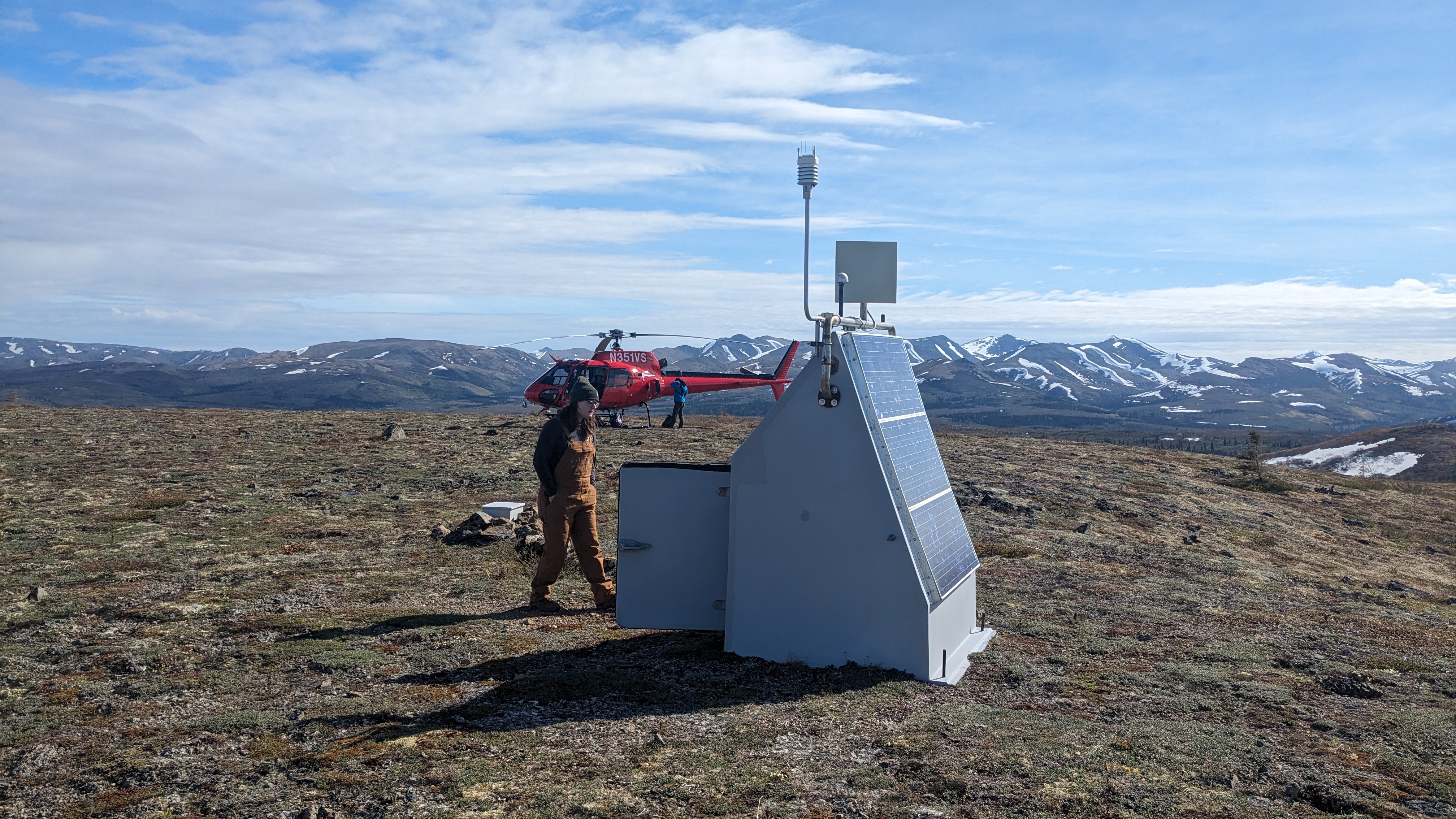

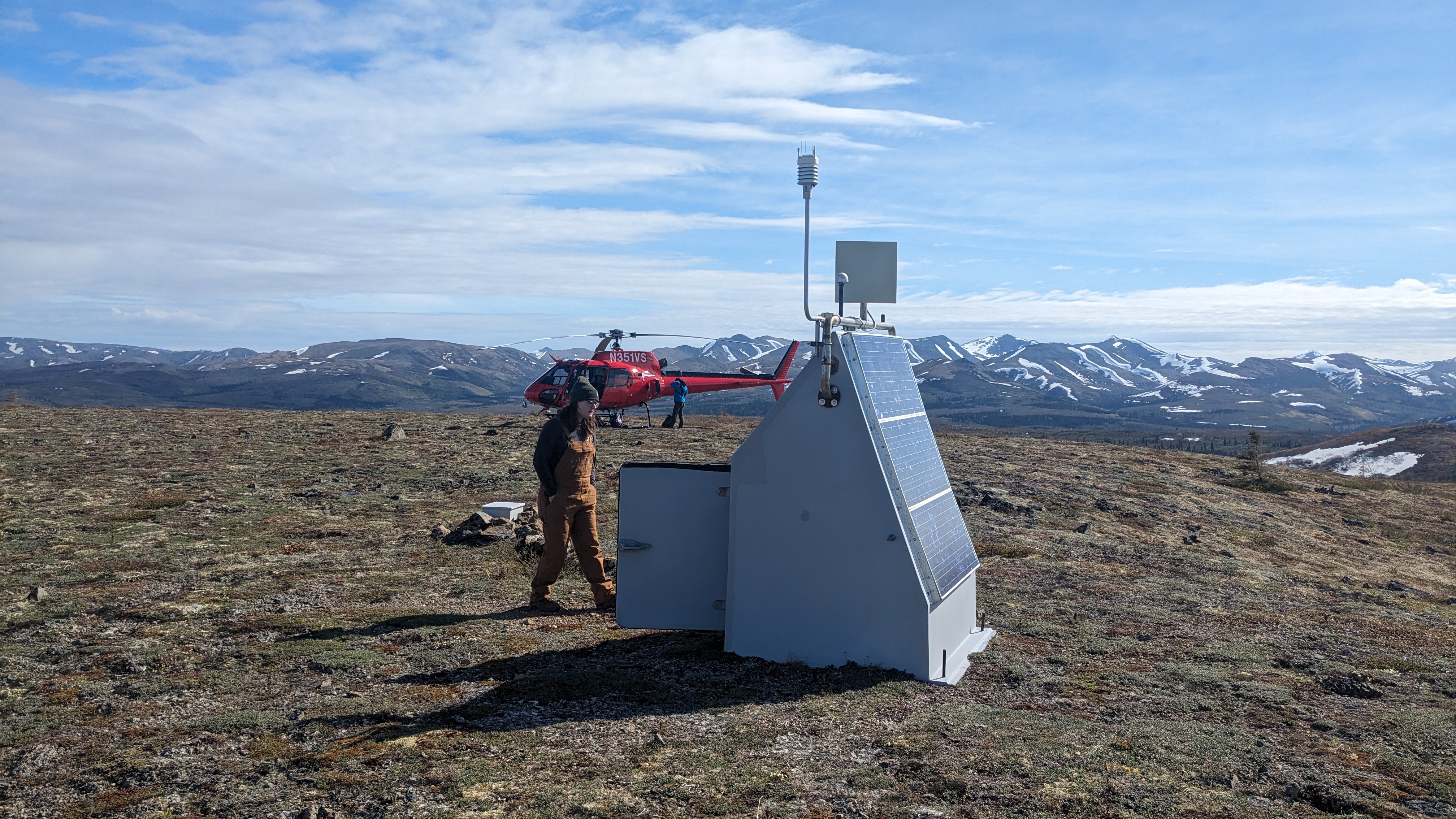

Field engineer Joanne Heslop collects data from and helps fix the Alaska Geophysics Network stations. “Our network of data allows us to capture changes in real time to inform policy, engineering decisions, and, more generally, how Alaskans are going to have to adapt to these ever-changing conditions.”

Heslop helps maintain the network stations during the summer field season, and assists in the research and development of the next generation of instrumentation. She stresses the significance of these stations, saying, “We play an important role in the region northwest of the Brooks Range because we are the only ones continuously monitoring year round and providing real-time, publicly available data.”

We currently operate 67 stations that provide real-time weather observations. Our Vaisala WXT520 and WXT536 weather instruments are installed two meters above ground and capture measurements for precipitation, temperature, humidity, barometric pressure, and wind direction and speed. When weather instruments are co-located with other instruments, like soil-temperature profilers and seismometers, a clearer and more complete picture of the processes surrounding the station site emerges.

If you are interested in learning more, contact us at uaf-aec@alaska.edu.