Figure 1. Gabrielle Davy and Earthquake Center researcher Ezgi Karasözen monitoring the Barry Landslide and Barry Glacier during a field visit, taking notes on observations of rockfalls on the slide area and glacier calving.

Figure 2. Davy attaching a temporary go-pro camera to record slope movement overnight on station BAE. The landslide slope is in the background on the left.

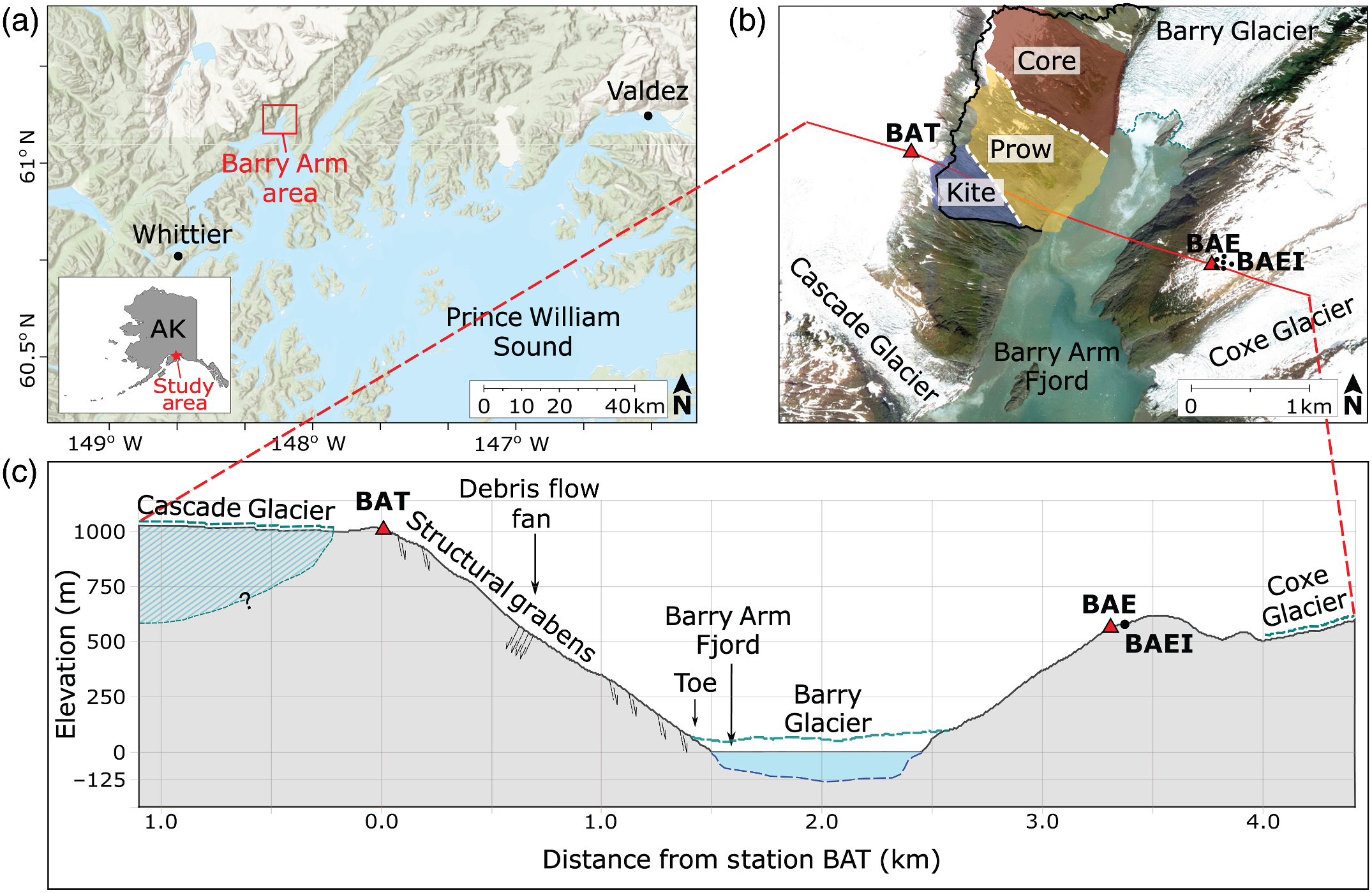

Figure 3. (a) Location of the Barry Arm area in relation to Prince William Sound and nearby communities, as well as location in relation to Alaska. (b) Barry Arm fjord detail showing the location of the Cascade, Coxe, and Barry Glaciers, as well as seismic stations BAT and BAE, and infrasound BAEI, and where the cross section is taken. The colored sections of the slope indicate the Kite (blue), Prow (yellow), and Core (red)—these locations are where the slope is most active. (c) Barry Arm fjord cross‐section diagram (1:1 scale) illustrating glacier features, fjord depth (slope profile derived from Google Earth; Google, n.d.), station locations, and structural features modified from Schaefer et al. (2023) Boundary for Cascade Glacier is inferred. (Figure and caption from https://doi.org/10.1785/0220250205.)

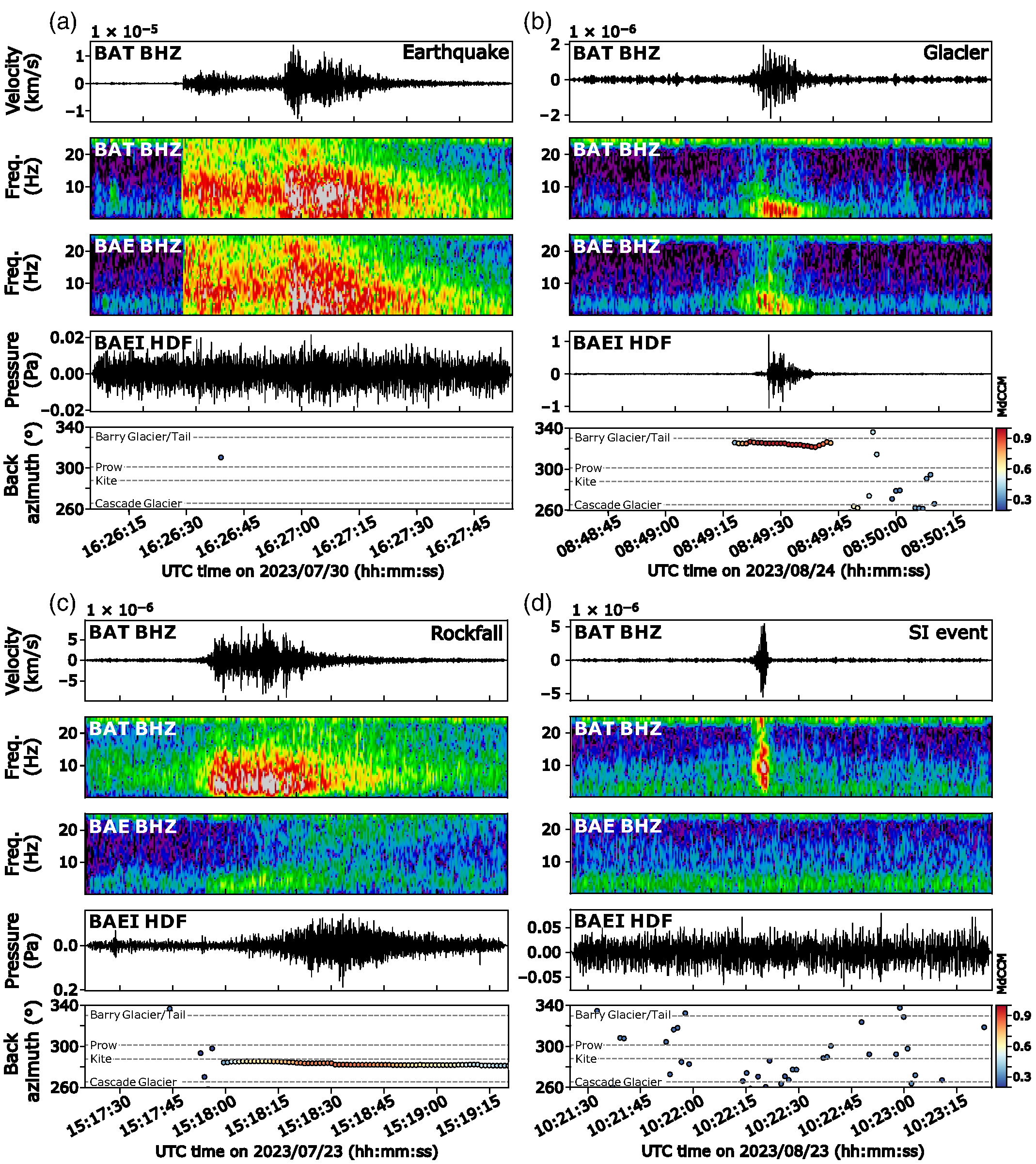

Figure 4. Seismogram, spectrogram, and infrasound (top to bottom) of an (a) earthquake, (b) glacier event, (c) rockfall, and (d) short‐impulsive (SI) event. Note that SI events do not appear on infrasound, nor station BAE, whereas rockfall and glacier events are present on infrasound and both seismic stations, and earthquakes are visible on both seismic stations. (Figure and caption from https://doi.org/10.1785/0220250205.)

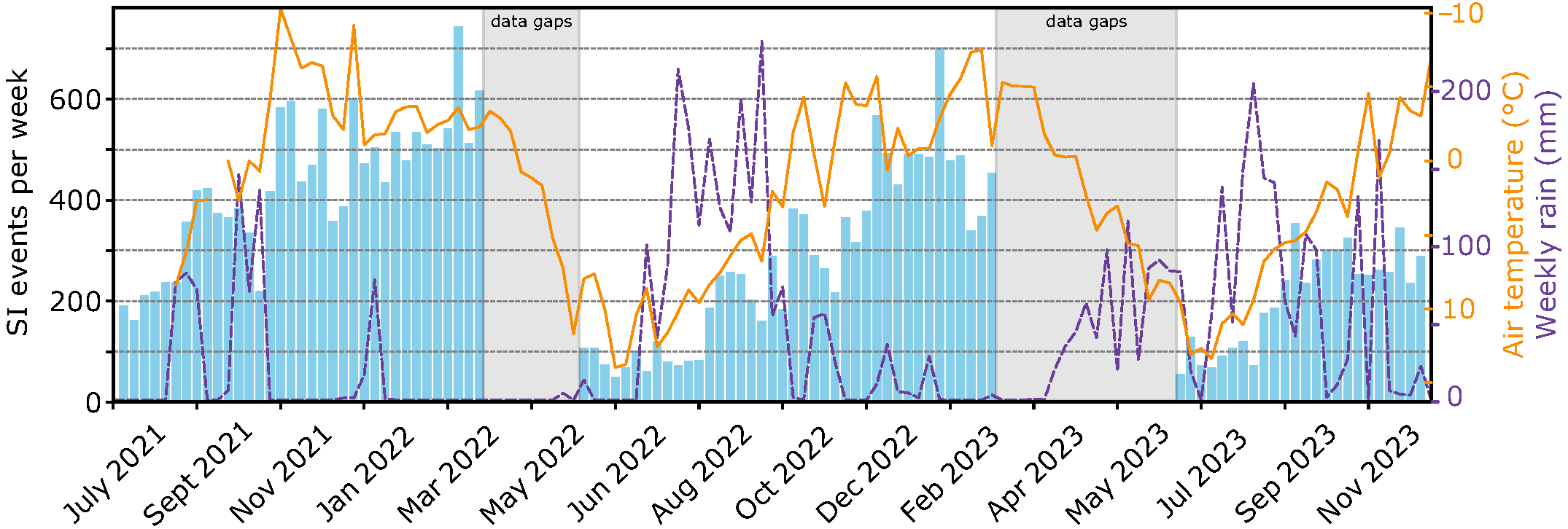

Figure 5. Histogram of SI events overlain with air temperature (orange) and weekly rainfall (purple) from July 2021 to December 2023. Note the data gaps in seismic stations from April to May 2022 and March to June 2023. (Figure and caption from https://doi.org/10.1785/0220250205.)

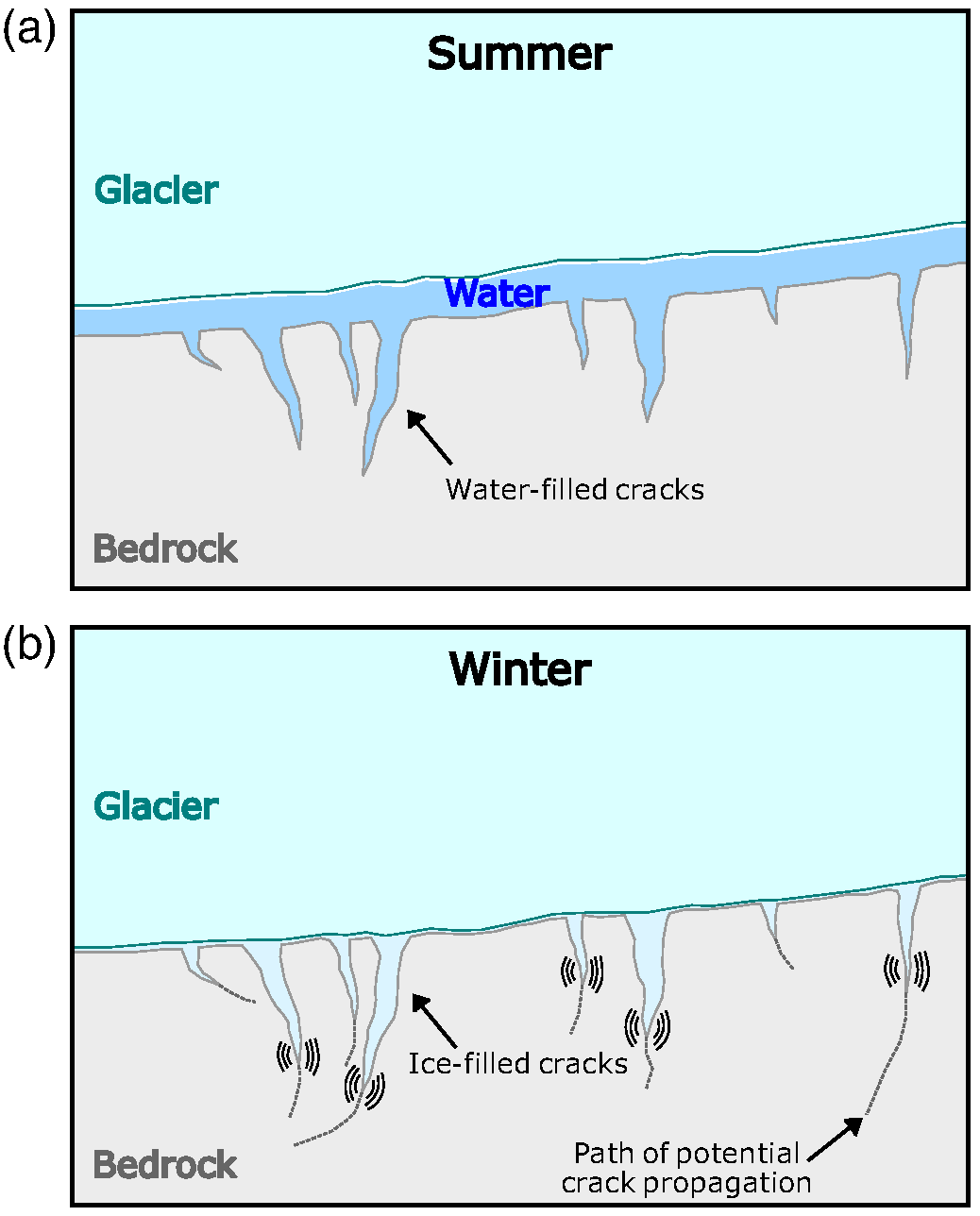

Figure 6. Seasonal “freeze‐up” cycle of subglacial (a) summer and (b) winter pathways. (Figure and caption from https://doi.org/10.1785/0220250205.)